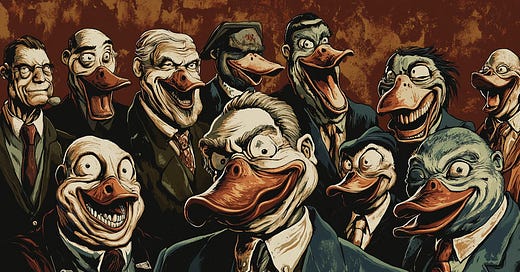

For the ordinary individual, unaccustomed to the machinations of the self-proclaimed elite, the insatiable hunger for power they exhibit remains an inscrutable puzzle: why would anyone expend such effort to subjugate their fellow beings or amass further riches when their wealth already surpasses what any lifetime could exhaust? This exploration does not aim to soothe with hollow assurances or drape their avarice in noble guise. Rather, it ventures boldly into the distorted recesses of their psyches, seeking to unravel the perverse impulses that propel them.

Here, you’ll find no sanitized platitudes—just a piercing examination of what drives their relentless pursuit, whether it’s the intoxicating thrill of shattering resistance, the parasitic satisfaction of draining others’ vitality, or a deep-seated frailty cloaked as supremacy. Envision this as a stark, unflinching map to their predatory nature, tinged with a wry edge to keep your curiosity sharp. We dissect their motives not for outrage, but to arm ourselves with the clarity needed to evade their grasp. The journey promises to provoke and unsettle—stay with it.

Substack is at risk of becoming another mindless scroll-fest like TikTok or Instagram, drowning out the thoughtful, long-form content we cherish. If you value real intellectual writing over clickbait, act now:

Like the work of authors you admire—every click boosts their visibility.

Comment politely to spark conversation and lift their reach.

Share your favorite pieces far and wide to drown out the shallow noise.

Tip or support financially to fuel the creators who matter.

Don’t let Substack devolve into cat videos and rants. Fight for its soul—starting today.

“I get the how, but not the why.” That’s Winston Smith, the beaten-down everyman from George Orwell’s 1984, scribbling in his secret little diary like it’s his last grip on sanity. He’s a grunt in the “Ministry of Truth” where his whole job is to twist history into whatever the Party wants it to be. Day in, day out, he’s forging the past, tweaking documents to fit the big lie. But something’s waking up in him, a quiet rebellion festering under the surface. It’s not loud yet, just a gnawing doubt that keeps him up at night, like a splinter he can’t dig out.

"What oppressed him with the sense of a nightmare was that he had never clearly understood why this enormous imposture was undertaken. The immediate advantages of falsifying the past were obvious, but the ultimate motive was a mystery."

So, yeah—why? You can’t wrap your head around freedom getting chipped away unless you wrestle with this thirst for power. Power’s the drug everybody wants but nobody admits to chasing. It’s a messy topic, slippery as hell. People love to slap “taboo” labels on sex and death and sure, depending on the vibe, those get shoved under the rug sometimes. But then they’re right back in your face: sex sells at the bus stop with some half-naked model, and death’s the nightly special on Netflix and Youtube—crime shows, body counts, disease stats. Power, though? It’s everywhere, woven into everything, but we barely call it out. We’ll yap about surface-level slugfests—Putin vs. Zelensky, Harris vs. Trump—but the essence of power, the dark shit driving it? Nope, crickets. It’s too ugly. Power’s tied up with control, submission, stripping people down—sometimes straight-up violence. It’s close to what you’d call “evil,” and I’m not shying away from that word.

If you skip power, though, you’re screwed trying to figure out humans. You might catch a glimpse of why we act the way we do—family spats, friend-group drama, office bullshit—but without power in the mix, you’re blind to the full picture. It’s like spotting the tip of an iceberg and pretending the hulking mass underwater doesn’t exist. People crave power over each other—need it, get off on it—and that sparks all the petty dominance games and manipulation we swim in daily. Why? Why does anyone want that leash on someone else? And why do we let ourselves get leashed?

Folks love tossing out “objective” excuses. “Oh, a crisis needs a strong hand!” Picture a house fire—nobody’s grilling the fire chief about his authority while the flames lick the roof. The average Joe, they say, can’t handle it—too dumb, too soft. He needs some elected bigshot (or a self-appointed one) to swoop in and play daddy. I’ll circle back to that later, promise.

But beyond emergencies, power can also come from something twisted—a hunger to dominate that’s borderline sick. Call it power-lust if you want. Good luck proving some politician’s drooling over it, though—it’s not like they leave receipts. Still, chasing that “why” cracks open doors. It might help us see the latest freedom-grabs for what they are.

Power’s trashed the world before—left smoking ruins and mass graves—and yet we rarely question it at its core. We’ll point fingers at this dictator or that tyrant, but power itself? Untouchable. If you want real critique, you’ve got to dig into the anarchists—guys like Horst Stowasser in his book Anarchy!. He’s quoting Bakunin, calling the state “an abstraction that devours people’s lives.” Stowasser’s not mincing words: the state’s a bully we’d never tolerate if it weren’t dressed up as “authority.” He’s like, “Imagine some rando trying to pull what the state does—taxing you at gunpoint, locking you in a cage for breaking their rules, or deciding you don’t deserve to breathe anymore. You’d call it nuts.” He’s got a point. We shrug off the state’s overreach because it’s “official,” but strip away the badge, and it’s just some asshole with a stick.

You could dodge that with “Oh, but the social contract!” or “Our lovely democracy!” Fine. Harder to defend, though, when you zoom out and see the atrocities the state has unleashed—centuries of bloodbaths, millions dead, all propped up by systems we built.

Stowasser doubles down: “Without the state’s fancy ideas and machinery, no lone psycho could ever rack up a body count in the thousands or millions. It’s absurd otherwise.” History backs him up—chaos isn’t the absence of power; it’s what power’s already given us. He’s raging: “Call anarchy ‘chaos’ if you want, but we’ve got that now—globally. Enough food to go around, yet thousands starve daily? Insane. Periodic mass slaughter? Inhuman. A system trashing the planet till it’s unlivable? Suicidal.”

Even if you skip the big stuff—wars, ecocide—power’s track record still stinks. Glance at history, and it’s a horror show: conquerors and conquered, breakers and broken, slavers and enslaved. Our species seems wired to stomp on free will, to let a few rule the many with a fist, then sell it back to us as the only way. The pitch changes—politics, religion, money, even “public health”—but the game’s the same. Always has been.

Here are some historical and current examples of these extreme forms of power, each draped in its own ideological costume. Take Murat Kurnaz, a German-Turkish guy held without charges in the U.S. Guantanamo Bay camp from 2002 to 2006. In his autobiography Five Years of My Life, he talks about befriending a lizard that kept sneaking into his cell. That little critter was his only “friend” in the soul-crushing isolation. His guard, an interrogation specialist named Holford, caught wind of it and ordered Kurnaz to kill it with his bare hands. Kurnaz refused. Weeks later, he ended up crushing the lizard with his body. How’d it come to that? Holford had been torturing him for weeks—pushing him to the edge with scorching heat, freezing cold, oxygen deprivation, and blasting unbearable music. Finally, he hinted at chopping off Kurnaz’s hand. That broke him.

I bring this up because it’s a perfect snapshot of the hollowed-out mindset of certain power-trippers. Funny thing is, Kurnaz later found a silver lining: once the lizard was dead, Holford had no leverage left. That’s when Kurnaz built some insane mental toughness—and survived.

Then there’s Turkey, probably the NATO champ at humiliating soldiers. It’s not rare—it’s standard—for troops to get brutalized by their superiors under the guise of “discipline.” Turkish feminist Pınar Selek, in her book Pampered into Men, Drilled into Men, collected interviews from dozens of ex-conscripts, shining a light on this hidden hell of psychological and physical cruelty. One guy said, “We’d bolt if we even saw the company commander from a distance. If he beat you, you couldn’t move a finger for ten days.” Another: “Sometimes he’d yank down your underwear to check if you’d shaved your privates. You had to stand there, freezing, rain or not. I was always ashamed.”

It starts with breaking recruits down, controlling every inch of their lives. Selek nails it: “Give up your own shape—take on the one they give you.” One ex-soldier put it like this: “When I took off my civilian clothes, I turned into a robot. From then on, I did what they told me. I knew my old life was over when they cut my hair.” That robot vibe screams military logic—think Star Trek’s Borg: you’re nothing, the collective’s everything.

The main training tool? Submission to rules. One conscript said, “Everything’s ruled. Sorry, but even on the toilet, there’s a sign: ‘Flush.’ You look in the mirror, and it says: ‘Fix your clothes.’ At meals, take off your beret. Before prayers, too.” So, on top of the machine-man ideal, grown adults get demoted to kids who can’t decide squat for themselves. In Germany’s Bundeswehr, they’ve got this gem: “Follow the road independently”—as if even independence needs an order. Or they’ll command “Winter!”—like snowflakes won’t fall without a sergeant’s say-so.

Now pivot to religious history for a different flavor of tyranny. From 1541 until his death in 1564, reformer John Calvin turned Geneva into a chokehold, propped up by his holy ideas. Stefan Zweig, in Castellio Against Calvin or a Conscience Against Violence, paints it vivid: “A state pulsing with life gets turned into a rigid machine, a people with all their feelings and thoughts crammed into one system.

It’s Europe’s first stab at total conformity, all in the name of an idea. That “idea” was virtue, per Calvin’s Bible-twisting. From day one, control slithered into every corner of life—and into people’s souls, where he sniffed out sin and godlessness.

He cooked up his infamous “discipline” or “church order,” which Zweig calls a “barbed-wire web of rules and bans.” Zweig writes, “Since Calvin’s return, every house has open doors, every wall’s suddenly glass. Day or night, a hard knock could hit your door, and a church cop shows up for a ‘visit’—no way to stop them.”Privacy’s dead.

Those “knockers” were morality spies, rummaging through homes and minds for slip-ups. They grilled adults like schoolkids—can you recite your prayers? Miss a sermon? They’d check women’s clothes and hair for anything “loose,” raid cupboards for banned books, even bitch about candy or jam—too joyful, too sinful. Holy pictures? Nope, too Catholic. On the streets, they’d perk up for forbidden tunes, not unlike the Taliban. Couples caught being sweet in public got chased off, mail got censored, snitches thrived. No theater, no festivals, no dancing, no games. Zweig sums it up with a line that feels ripped from today: “Forbidden, forbidden, forbidden”—a grim beat.

Now, something closer to today. In 17th-century France, the plague tore through, and the “medical emergency” rules were brutal. City gates locked, leaving was a death sentence. Towns got carved into zones, each with an “intendant” or “syndic” running a tight ship. On bad days, everyone stayed indoors. Soldiers patrolled. Lowlifes hauled off corpses. Syndics bolted houses shut from the outside. Daily, a block warden banged on windows, called every name, checked who’s alive. No answer? Plague suspected.

Michel Foucault, in Discipline and Punish, lays it bare: “Space freezes into a grid of sealed cells. Everyone’s pinned to their spot. Move, and you risk death—disease or punishment.” Foucault wasn’t just chronicling health policy; he was exposing how states have watched and squeezed their people forever. His big take: power naturally guards itself, grows, tests itself on the helpless—emergency or not. In that plague-ravaged city, an old political fantasy came true: “rules seeping into life’s tiniest details, enforced by a hierarchy that keeps power humming to its edges.” Or, simply, “the utopia of a perfectly governed society.”

One of the most widespread circles of oppression—then and now—is the prison system. Prisons are often overcrowded, cranking up the claustrophobia and tension among inmates. They’re notoriously short on beds. You’re usually crammed into a cell with multiple others. TVs blare from morning to night. The food’s lousy and unhealthy. In one women’s prison, a toilet sat smack in the middle of an eight-square-meter cell for four inmates—everyone doing their business in plain view. Rats sometimes crawled out of it. Violence between prisoners is common, with scores often settled under the showers. Guards mostly look the other way, or victims stay quiet, fearing retaliation.

The suicide rate inside is seven times higher than outside. Hanging’s the top cause, followed by self-set cell fires.” The system, of course, has a response for suicidal inmates. Those at risk get tossed into a fully video-monitored room with just a thin mattress and a toilet to round out the setup.” You can imagine how being stuck in a place like that—also used as harsh punishment for violent or defiant inmates—affects the “recovery” odds for desperate, depressed people. These cells are psychological torture, slamming shut even the last escape route: suicide.

You could stretch this grim tour of power abuse endlessly—pivot to “boot camps,” conditions in fundamentalist Islamic countries, Great Britain’s concentration camps, or the vast horrors of Nazi Germany or Soviet atrocities. The picture’s always the same: brutality, callousness, and what looks like gleeful violence.

No oppressive system, no matter how vile, has ever collapsed for lack of enforcers—thugs and lackeys ready to do the dirty work. Jobs that require a knack for tormenting and crushing others seem to hold a magnetic pull for some. Sure, you could point to personal reasons for why someone becomes a guard, a drill sergeant, a torturer—maybe social rejection, maybe their own trauma. A “virus of cruelty” might even pass down through generations. But pop psychology alone can’t explain the sheer scale of terror that’s stained every era and continent.

The darkest secret of humanity still waits to be dragged into the light.

Before I plunge into the heart of darkness: What kind of power am I even talking about? This definition is not the only one possible, and my thoughts on power won’t be boxed in by it, but it’s a rough guide to get us going.

Power is the ability to make someone do something they originally didn’t want to do, or to stop them from doing something they intended to. This take on power sits close to “coercion” or “force,” and we won’t get far with softer spins.

Dodgy definitions like “Whoever acts has power” or vague talk of “responsibility” and “duty” miss the mark. If I nudge someone into behavior they’re already happy to do, that’s not power. Even convincing a doubter to see my side isn’t power—it’s persuasion, an art that flirts with the “power of words” but doesn’t hit the core of what I’m digging into here.

“You only need power if you’re up to no good. For everything else, love’s enough,” Charlie Chaplin said. In this context, power’s mostly about force: the knack for breaking a will, pushing someone to do something they’d flat-out rejected—not because they want to, but because they grudgingly give in. That’s how a vaccine campaign rolls, for instance.

First off, we’ve got to clock that power comes in two flavors: constructive and destructive. Erich Fromm’s got some sharp insights on this in his book To Have or To Be. He splits authority into “rational” and “irrational.”

“Rational authority boosts the growth of whoever trusts it and rests on competence. Irrational authority leans on power and exists to exploit those under it.”

Think of a loving mom or a kind teacher—folks who steer things for the kid’s sake, no selfish agenda or power trip, maybe getting strict when needed. But it’s not just pure-hearted vibes that make this work; the one in charge has to actually be an authority.

“Authority rooted in being isn’t about ticking societal boxes—it’s tied to a person’s character, someone who’s hit a high level of self-realization and wholeness. That kind of person radiates authority without threats, bribes, or barking orders.”

On the flip side, there’s authority handed out by a formal pecking order.

“With societies built on hierarchy—way bigger and messier than hunter-gatherer crews—authority based on skill gets swapped for authority based on status. That doesn’t mean the new authority’s always incompetent; it just means competence isn’t the point anymore.”

Put another way: Any clown can grab power, but not every clown’s got the chops to be a real authority. And they’re damn sure not a blessing to whoever’s stuck under them.

A king—like that clown on the British throne—can be dim, sneaky, rotten, totally unfit to lead, and still have authority. As long as he’s got the crown, people assume he’s got the goods to back it up. Even if the emperor’s buck naked, everyone swears he’s in fine threads.

What’s wild is that back in 1976, when To Have or To Be dropped, Fromm was already calling out the stories propping up power:

“It’s not automatic that people see uniforms and titles as proof of skill. The ones holding authority—and those cashing in on it—have to sell that fiction, lull people’s sharp, critical thinking to sleep. Every thinking person knows propaganda’s tricks: ways to shred judgment and numb the mind till it bows to clichés that dull people down, make them dependent, strip them of trust in their own eyes and reasoning.”

I find Fromm’s distinction useful, though I’m not thrilled with tagging authority as “rational” or “irrational.” Even a perfectly “reasonable” person who climbs to power through orderly means can wreak havoc. That’s why I prefer “constructive” and “destructive”.

What’s intriguing is that Fromm ties “power” only to what he calls “irrational authority.” He sees orders and threats as the rot of real authority—crutches for weak “commanders” who’ve got no better tools. Power only kicks in when authority flops or when unfit people with formal clout insist on ramming their will through.

You’ve got a natural power over your partner just by affecting their mood—whether you meant to grab that power or not. Every word, every move you make “does something” to them—lifts their spirits, ticks them off, or worries them. If you walk out, you’re cutting a deep, painful gash into their life. They’ve got the same power over you. Whoever loves less or holds a stronger social perch often ends up with the upper hand. Natural power’s tied to being loved or needed in some way.

Parents, of course, have natural power over their kids. And anyone who’s ever felt “bossed around” by their own children—especially tiny ones who rob you of sleep for months—knows kids wield power over parents too. Anyone we care about or have to look after holds power over us—people we’re tied to, willingly or not, in setups we can’t just ditch. That goes for cliques, friend groups, work crews. Power comes from whoever’s a force in our lives—someone whose approval we can’t afford to lose. They can push us into stuff we didn’t want through emotional, moral, or legal pressure. That’s not inherently bad if it’s just daily duties or fair claims others have on us. We change a baby’s stinky diaper, we slog through a job we’re not feeling some days—because we signed a contract and figure it’s worthwhile overall.

Czech writer Milan Kundera, in his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, digs into this power from people who matter to us. He drops a key observation: how we talk is always shaded by the power dynamic with whoever’s across from us. We don’t just hold back with a wild self-expression spree around the boss—partners, close friends, and family get kid-glove treatment too, since we don’t want to lose them. We want to keep things good long-term.

Throw in a stark power gap, and communication can turn toxic—arrogance on one side, groveling caution on the other. With hardcore intolerant bosses or “authority” figures, free talk dies altogether. The “stink” of power—and the fear of it—literally chokes the weaker side.

Flip that around: When someone’s no force in my life, when they’re beneath me or flat-out powerless, they’re a damn good fairness test. Those moments dare us not to exploit the gap in our favor. Kindness shines when we’ve got nothing to fear or gain from the other person—no punishment for screwing up, no perks for playing nice. The real challenge comes from those at the bottom of the heap, whose company means zilch to us, who we could mistreat without a single consequence.

Provocateur director Lars von Trier ran a fictional social experiment in his 2003 film Dogville. Grace (Nicole Kidman) flees the cops to a remote mountain village. The locals know she’s in a tight spot. To avoid getting ratted out, Grace offers to do all kinds of work for them. Things spiral: the villagers exploit her labor more and more shamelessly, chain her up like a dog to stop her escaping—then the men rape her.

Von Trier’s grim takeaway: Left to themselves with no legal leash, average folks turn into “monsters” who ruthlessly flex their power over the weak, no mercy. You can argue whether his blanket verdict on humanity holds up. But peek at the world’s holding camps, boot camps, barracks, reform homes, slaughterhouses (or maybe just at how a bunch of conservative or liberal assholes, digitally abuse someone online, simply because they dared to criticize something they hold dear)—Dogville’s plot isn’t exactly plucked from thin air.

Even amidst its grotesque excesses, let’s get one thing straight: power isn’t some rare beast skulking in the shadows—it’s as mundane as your morning coffee, woven into the fabric of daily life. To call it inherently “evil” is lazy nonsense.

Picture a kitchen knife: you can slit a throat or slice bread—same tool, different intent. What Erich Fromm dubs “rational authority” isn’t some optional frill; it’s a stubborn constant of existence. One teaches, another learns; one leads, another follows; one’s strong, another’s weak; one’s free, another’s tethered. Power saturates our every interaction, so baked into the routine that we barely notice it—like air, it’s just there. Escaping it? Good luck. You’re not dodging it as the one wielding it, nor as the one under its thumb.

We’re born into a world of rules, edicts, and bans we didn’t write or sign up for—yet here we are, playing along. And don’t kid yourself: slipping into a mid-level “department head” gig after a few years on the job doesn’t take ruthless ambition or sharp elbows—just a pulse and a resume.

So, tell me—how do you even dream of outrunning power? Make noise, and you’re flexing it, forcing someone’s ear and mind to endure your racket. Complain about the noise, and you’re still at it, asserting your will.

Put up a street sign—power. Cut someone off in traffic—power. Push for a conversation—power. Duck someone’s attempt to connect—power. Show up late—power. Chew someone out for being late—power. Drown them in a wordstorm—power. Freeze them out with silence, devaluing them—power. Grocery shop for the family? You’re the dictator of the menu for days. Skip the shopping? You’ve just strong-armed the rest into picking up your slack. Torment someone mentally—power. Wallow in loud suffering to guilt-trip them—power. On and on it goes.

Most of this is small potatoes, harmless quirks of human messiness. Even the power-wary among us can’t sidestep it in the day-to-day grind. But what I’m zeroing in on here isn’t this petty dance—it’s power that surges past any sane limit, the personal and structural chokeholds, the grossly lopsided imbalances. I mean the crushing weight of state machinery, corporate titans, church dogmas, “superiors,” and self-appointed overlords—the destructive, abusive kind.

Too often, power’s just disrespect with a fancy title. It thrives on trampling the other guy’s autonomy, puffing up your own interests and worldview like they’re the only ones that count. Bolt it into a hierarchy—slap on some titles and offices—and that disrespect gets a golden stamp of legitimacy.

What’s really a fragile ego screaming, “I need this, damn it,” gets dressed up as “It’s forbidden” or “It’s mandatory.” Suddenly, the whims of individuals or cliques—whether sensible or deranged—gain this fake sheen of objectivity, and nobody dares question it.

Look at economic theory: power’s the grease in capitalism’s wheels, concentrating wealth and control while pretending it’s “merit.” Political realism backs this up—states don’t coddle; they dominate, because that’s their DNA. Those who cheer power as some noble force are deluded—it’s a bully’s game, not a savior’s.

Power’s only tolerable under razor-sharp conditions. Imagine a standoff where both sides pack equal punch—symmetry, not servitude. Picture a wielder obsessed with power’s dark side, not blind to it, paired with a gut-level respect for the other person, no matter their rung on the ladder. Add empathy, a knack for self-doubt, and a tether to consequences—where the “powerful” can’t dodge the fallout of their own moves. Tie it to real skill, not just a corner office, and strip out any whiff of twisted pathology. Miss any of these, and power’s not just risky—it’s arrogance on stilts, a trespass we’ve got to fight tooth and nail.

Take a practical jab: governments love preaching “public good” while hoarding control—think tax codes or lockdowns, sold as duty but reeking of overreach. Corporations play the same card, squeezing labor for profit while waving the “job creator” flag. It’s a con, and we’re the marks unless we call it out.

“The most essential prerequisite for this unprecedented concentration of power,” declares historian and philosopher Daniel Sandmann in his essay The Shifting of the World, “is the systematic erasure of any awareness of power itself.” If we don’t claw back that awareness, we’re nothing but lambs bleating helplessly before the slaughterhouse of the powerful.

What I’m calling “power-lust” here is the dirty little secret, the missing piece that ties together the puzzle of colossal human screw-ups—whether it’s one tyrant’s tantrum or history’s grand parade of atrocities. It’s the hulking elephant stomping through the room: blindingly obvious yet somehow invisible to most, or at least too taboo to name.

“We don’t talk about that,” they whisper, clutching their pearls. But cast your eyes back over the nightmares we’ve already dissected—Calvin’s reign of terror in Geneva, Guantanamo’s sadistic circus, the meat-grinder of military training across the globe. Explain those without factoring in the sheer thrill of power? Good luck. You’d have better odds selling trickle-down economics to a soup kitchen.

So what’s ticking in the warped minds of those perched atop these hierarchies? And why do people—without a gun to their heads—keep volunteering as lackeys for these soul-crushing systems?

There’s a bizarre prudishness around power. Among the world’s big shots, you’d think not one ever craved it—at least if you swallow their sanctimonious press releases. “Responsibility” weighs oh-so-heavy on their noble shoulders; they’re just itching to “shape things” or “give back” to the land that’s showered them with riches. It’s all about leaving the world better than they found it—selfless saints, every one. With such angelic motives, Earth should be a utopia by now, right? Cue the bitter laugh: it’s a cesspit.

Politicians peddle this fairy tale that they only stumbled into power because their buddies begged them to. Once they’re cozy in the throne, not a peep escapes hinting that wielding it might actually be fun. Imagine the rush: standing at a podium, decreeing that next week every citizen must strap on a face mask—and then watching millions obey like magic. It’s a Saruman moment straight out of Lord of the Rings—the wizard atop his tower, barking commands, while below, thousands snap into perfect ranks, moving as one massive beast to his tune. Don’t tell me that doesn’t spark a shiver of glee in some of these suits.

Even at something tamer—say, a Fridays for Future rally—you can catch a whiff of this weird intoxication. Teens, drunk on the spotlight, scream through megaphones with cracking voices: “What do we want?” The crowd roars back, “Climate justice!” “When do we want it?” “Now!” And most don’t bat an eye at drowning in the herd. Why would they? Who’d dare argue against climate justice? It’s noble, unassailable—until you notice the puppetry of it all. Power’s pull doesn’t need a villain’s cape; it works just fine in tie-dye.

Let’s rewind to Winston Smith’s haunting question in 1984: “I get the how, but not the why.” Near the novel’s end, the system’s loyal torturer, O’Brian, picks up that thread. Smith’s strapped down, helpless, while O’Brian toys with a machine that can zap him with agonizing shocks. In a twisted bonding session, the bastard prods his victim to philosophize about why anyone builds such a monstrous regime. “What’s our motive? Why crave power? Speak!” Smith, desperate to appease, stammers a flattery: “You rule us for our own good. You think people can’t govern themselves, so…” Zap—O’Brian fries him with a jolt. “Be honest,” he snarls. Then he lays it bare: “The Party seeks power solely for its own sake. We don’t give a damn about others’ welfare—only power, pure and simple. Not wealth, not luxury, not long life or happiness—just power.” With a jab at socialist tyrannies, he adds, “No one seizes power planning to let it go. Power isn’t a means; it’s the endgame.”

O’Brian doubles down: real power demands the individual vanish into the collective. “First, grasp this: power is collective will. A person only has power when they stop being a person. It has to be that way—every human’s doomed to die, the ultimate flaw. But if they can fully submit, shed their self, melt into the Party until they are the Party, then they’re almighty, immortal.” He defines it starkly: “Power is power over people. Over the body—but above all, over the mind.” Orwell’s brutal vision casts power as its own reward, torching any pretense of “higher purpose”—especially the laughable lie of citizens’ “happiness.”

Sure, 1984’s fiction, but sharp writers like Orwell don’t just spin yarns—they excavate truths, peeling back reality’s skin. Let’s run with this as a working theory: some crave power for its own sake, a raw, selfish end. That lens cracks open a lot.

Take the ultra-rich—why hoard billions when they’ve already got enough for every need and luxury? Power-lust fills the gap; money’s just the scorecard. Or consider power’s chameleon act—dressing up one day as religious zealotry, the next as socialist or fascist iron fists, then as a “democratic” security-and-health clampdown.

Economic theory backs this: concentrated power drives markets and states alike, from monopoly crony-capitalism to authoritarian control—profit and domination are two sides of the same coin. History’s horizon now teases new costumes: a tech-fueled, “transhumanist” surveillance fascism looms. Same game, shinier toys. Point is, power doesn’t need a noble mask—it thrives naked, and we’re fools to buy the PR.

Orwell doesn’t just leave us with a dystopian slugfest—he cracks open a psychological window into why people fling themselves headlong into collective straitjackets. It’s not just for the party hacks or power cliques; it applies to the average Joe too. The individual, he says, yearns to “escape their own self” and dissolve into something bigger—the Party, the State—sidestepping the sting of their own mortality. That bigger thing, once you submit, feels immortal.

Remember the Nazi propaganda plastered on Hitler Youth barracks: “You are nothing—your people are everything”? That’s the playbook. Strip away the self, and death’s shadow shrinks. It’s a seductive trade-off, especially if you squint at it mystically—swap the “ Volk” or Party for a religious flock or God Himself, and you’ve got the mystic’s dream of melting into the divine like a drop in the ocean.

Fascist collectivism? It’s the cheap knockoff—a pseudo-spiritual fix for a godless, materialist age. The “ Volkskörper” struts in as a DIY deity, feeding a hazy longing to merge, driven by dread of death and the gnawing ache of being small and breakable.

Let’s zero in on the puppet-masters. Power isn’t some noble response to the downtrodden’s pleas or “objective” necessity—it’s a craving festering in the powerful themselves, more often than their PR flacks admit. Sure, real-world kingpins might blend murky motives with half-baked ones—the urge to “shape” things, the smug nod that a crisis demands a firm hand—tangled up with raw vanity and a bare-knuckled drive to dominate.

You see the same cocktail in everyday tyrants: the petty despots ruling households with an iron glare. That’s why I will drag Natascha Kampusch into this—kidnapped at ten in March 1998 by Wolfgang Priklopil, a telecom tech turned jailer. Eight-plus years she spent, mostly in a basement dungeon, a guinea pig in his twisted power lab. Her book 3096 Days spills the grisly details with a clarity that cuts. It’s a perfect case study: one “ruler,” one “subject,” no messy social web—just a stark, isolated power dance.

Kampusch’s ordeal reeks of a pathological itch only Priklopil could scratch. “I always wanted a slave,” he bragged to her, no shame. “I’m your king,” he’d crow, “and you’re my slave. You obey.” Her take? “He wasn’t subtle—he wanted power, loud and proud.”

Writing four years after clawing free, she bends over backwards to be fair, even-handed, and digs for motive: “I think Wolfgang Priklopil, through this awful crime, just wanted his little perfect world, someone all his own. He couldn’t get that the normal way, so he decided to force it, mold it. Deep down, he wanted what everyone does—love, recognition, warmth. He just couldn’t see any path but kidnapping a shy ten-year-old, cutting her off from everything until he could ‘recreate’ her.” Her spin’s a gut-punch: total control over a helpless soul as a stand-in for love. Power as a warped consolation prize for those who can’t hack the real, mutual kind.

Cue Wagner’s Das Rheingold—love and power slugging it out as oil and water. The dwarf Alberich dives into the Rhine, lusting after the gorgeous river nymphs: “I’m mad for you—one of you will cave.” They laugh him off, mock his ugliness, shove him away. So he curses love, snags the Rheingold, and forges the ring of power.

The prophecy’s clear: “Only he who renounces love’s might, who banishes its delight, can wield the magic to shape the gold into a ring.” Love’s out; world domination’s in. The myth pegs power-lust as scorned affection’s bitter fruit—destructive power demands a loveless core. You’ve got to kill off any hunger for a healthy, equal bond to play tyrant.

Erich Fromm nails it in Escape from Freedom. Modern woes—alienation, rootlessness—stem from a symbiosis itch. Kicked out of tight-knit clans, tribes, or faiths—call it Eden’s eviction—we’re adrift, aching to “escape the self,” as Winston Smith put it. Pain, shame, loneliness gnaw; we chase a “bigger self” to melt into. When real love’s blocked, you get warped symbiosis—connections that blur the “I” without the warm fuzzies.

Sadism’s one flavor: the sadist craves fusion with others into a super-organism but insists on steering the ship solo. He’s in the boat with the rest, sure, but they don’t get a say on the course—equals on paper, pawns in practice. It’s a clumsy mash-up of two drives: dodging isolation and clutching control. In a decent romance, you throttle back dominance for the joy of togetherness. Life’s choice is stark: solo, with total freedom, or paired, bending to others’ needs.

Fromm unpacks sadism in Anatomy of Human Destructiveness:

“The core of sadism, across all its forms, is the passion to hold absolute, unchecked sway over a living being—animal, child, man, woman. Forcing someone to endure pain and humiliation without resistance is one face of that dominion, but not the only one. To fully master another is to turn them into a thing, your property, while you become their god.”

It’s a botched stab at beating loneliness—expanding a stunted self by swallowing the subjugated, stripping them of dignity, reducing them to tools. Fromm calls it “clay in the potter’s hand.”

The sadistic power freak wants it both ways: connection and total command. The more broken and pliable the underling, the tighter the symbiosis feels. The perfect pawn won’t flinch at an order any more than your hand balks at grabbing a cup—or hesitate to slug a foe any more than a glove resists a fist.

For Priklopil, Kampusch was an extension of his shriveled ego—a fix for feeling “too small.” Scale it up, and some overlords see a whole nation as their bloated self. The passive, crushed “members” of this twisted union lose their personhood—no feelings, no rights, just props. They’re “someone” to soothe the tyrant’s need for company, but “no one” to challenge his whims. In his eyes, they’re not subjects with their own worlds—just clay. Look at history’s tyrants: Stalin’s purges, Mao’s millions—collectives as meat for the grinder, not souls worth a damn. That’s the game, and it’s no accident.

Here’s the stark truth these musings unearth: the sadist leans on their victim far more than the victim ever relies on them. Take Wolfgang Priklopil—when Natascha Kampusch bolted in 2006, he didn’t just sulk; he offed himself. Erich Fromm cuts to the chase in Escape from Freedom:

“The sadistic person desperately needs the one they dominate, because their own sense of strength hinges on ruling someone else. This dependence might lurk below their radar entirely.”

Genuine love? Out of reach for them—though they might kid themselves that the twisted grip they’ve got feels like it. Fromm doubles down:

“They might fancy they only want to control her life because they love her so much. But truth is, they ‘love’ her because they control her. Ruling someone while claiming it’s for their own good can look like love—but the real kick comes from domination.”

Torture and murder? Just the uglier end of the same stick—bloody proof of their supremacy. Fromm again:

“If I can kill another, I’m ‘stronger.’ Yet psychologically, this lust for power doesn’t spring from strength—it’s weakness screaming. It’s a frantic grab for fake toughness where real grit’s missing. Impotence—not just in the bedroom, but across all human potential—drives this sadistic power chase.”

Rarely does anyone cop to this power-lust straight-up—except maybe Robert Ley, Nazi labor front boss, who crowed: “We want to rule, we delight in ruling… These men learn to ride, say, just to feel a living thing totally under their thumb.”

Thomas Hobbes, in his 1651 Leviathan, doesn’t flinch either: humans are wired for “a perpetual and restless desire for power after power, ceasing only in death.” That’s not just sadists—it’s all of us, he says.

Then there’s Nietzsche, going full barbarian in The Antichrist:

“What’s good? Everything that boosts the feeling of power, the will to power, power itself in man. What’s bad? Anything born of weakness. What’s happiness? The sense that power’s growing—that resistance is being crushed.”

That last bit’s a neon sign: power’s a beast that needs to flex, expand—never static, never sated. No “for the people” fig leaf here—just naked appetite. Nietzsche piles on:

“The weak and botched should perish: first rule of our love for man. And we should help them along.”

Charming, right? Political realism eats this up—states don’t plateau; they metastasize, gobbling territory and minds, because stagnation is death.

That growth itch explains why the powerful never quit. The local party chair gunning for prime minister, the prime minister eyeing president or EU kingpin—hit that, and they’re still itching to steer NATO and puppet-string peripheral nations. It’s not just about stacking up more minions; it’s about digging deeper, hollowing out the subject until they’re a husk—no pesky will left to snag on.

The dream? A Roomba with a pulse—obedience so seamless it’s robotic. The ruler’s whims should flow straight to reality, no friction, no filter. Subordinates should resist as much as air resists a dropped brick—meaning not at all.

Orwell nails this dual thrust in 1984: “The Party’s twin goals are to conquer the whole Earth and wipe out independent thought for good.” Breadth: stretch the empire’s borders. Depth: colonize the subject’s skull until their original self’s gone, replaced by the master’s will. Total compliance, total scale—anything less, and there’s room to climb. Look at history: Rome didn’t stop at Italy; it swallowed the Mediterranean. Modern states? Same game—global reach, thought police included.

Hannah Arendt pegs the tyrant’s hallmark as “the will to power, pure and simple.” No grand passion to shine, no pretense of uplifting the masses—just power for power’s sake. “It’s not a means, it’s the end,” she says, echoing Orwell’s O’Brian but with a philosopher’s icy remove. She’s not mincing words: this isn’t some quirky political vice—it’s a cancer that guts civic life entirely.

Contrast that with the bleeding hearts who swear power’s a tool for good—nonsense. It’s a machine that chews up freedom and spits out control, whether it’s a dictator’s boot or a bureaucracy’s clipboard. States and their apologists peddle “order” or “welfare” as bait, but the gears grind the same way—more turf, tighter grip.

Bringing “sadism” into the ring prompts a sharp question: does this lust for power carry a sexual charge, or even stem from it? Erich Fromm sidesteps the bedroom—his sadism isn’t about getting off on physical cruelty. It’s a mental-emotional high, a perverse joy in lording over others.

Sexual sadism—and its flip-side, masochism—are narrower kinks, less common than the broader dance of dominance and submission in politics or society. Still, peeking into this “playful” corner where control gets acted out is worth the detour. Take Fifty Shades of Grey—E.L. James’s three-part S&M soap opera. It moved 20 million copies worldwide in its first sales blitz, with a glossy film trilogy hot on its heels. That kind of runaway hit screams something about the society lapping it up. What grips me isn’t the literary dreck but the eerie overlap between sexual sadism and political domination. Don’t be fooled: this yuppie bedroom saga isn’t about whip-cracks. It’s mundane stuff—rules, breaches, punishments—dressed up as spicy.

The “hottest” erotic novel of our time reads like a dry legal brief at points:

“The Sub obeys all the Dom’s orders without hesitation, unconditionally, instantly. The Sub consents to any sexual acts the Dom deems appropriate and pleasurable, barring those listed under ‘Hard Limits.’… Any breach of these terms triggers immediate punishment, its nature set by the Dom.”

Christian Grey’s rulebook for Anastasia Steele—Dom and Sub, short for submission—feels like a spoof of contracts micromanaging every twitch. Harmless fun, you say, if power games juice up the thrill? Think harder. The real jolt is realizing domination can feel good. It’s pleasure fed by cruelty—dishing it out or taking it.

The Fifty Shades craze synced with a creep of real-world authoritarianism—funny, that. Back when moralists clutched pearls over “perversions,” now media practically shoved S&M down our throats as a bedroom perk. Who’d risk being a “bore in bed” next to Sexy Christian? But submission here doesn’t spark life—it strangles it.

Power, as framed, turns the sub into a thing. Their “contract” spells it out: “The Dom accepts the Sub as his slave, to possess, control, dominate, and discipline during the term. The Dom may use the Sub’s body as he sees fit, sexually or otherwise… The Sub accepts the Dom as her lord and master, viewing herself as his property.” Swap “Dom” for “State” and pause for a moment.

Power hunts total control. Those chasing it are too frail to face an unrigged game—pathetic, really. Flip that: the power-hungry are likely warped, hollowed-out wrecks, not robust souls embracing life. That both sides—dominator and dominated—can relish the grind doesn’t debunk this. Lust and love get twisted into bait, luring us past natural recoils at being objectified.

Christian purrs to Anastasia: “The line between pleasure and pain’s razor-thin. Two sides of a coin—one can’t exist without the other. I’ll show you how sweet pain can be.” The masochist gets a payoff—beyond the rush of ditching self-control—hitting a pain threshold that flips to ecstasy. S&M guru Matthias T.J. Grimme calls it “the knack for experiencing and savoring pain as erotic fuel.” For the doms? “Many feed off the emotions they stir—relishing the power to push someone sexually further.” Economic logic tracks: neoliberalism breeds control freaks—CEOs, not creators, thrive. Politically, states bank on fear, not freedom—compliance is the currency.

Christian Grey’s world oozes this vibe: a slick billionaire in a tailored suit, meeting Anastasia in a sterile glass-and-steel office tower—peak neoliberal poster boy. Society’s been bowing to this type for decades, trailing Anastasia’s lead. He’s cocky, a touch smug, but sprinkles in “care”—a boss you can lean on, offload your burdens to, from scene one.

Gender matters here: he dominates, she submits. The books hint women, weighed down by emancipation’s “burden,” crave shedding will. I call bullshit—that’s not a “woman thing.” Society as a whole, men included, drools for submission. Look at 2020’s COVID mess: unease with modernity’s rootless grind—thanks, commodity culture—drove us to ditch freedom’s weight for new shackles. Safety obsession, fanned by state and media, tempts us to trade liberty for a cuddle. Health scares turbocharge this spiral. Sadism mirrors authoritarian rule; our groveling to “safety” reeks of masochism.

Christian’s early pitch to Anastasia lays the political subtext bare: “I have rules you must follow—for your benefit and my pleasure. Obey to my liking, and I reward you. Disobey, and I punish you—you’ll learn.” Sound familiar? It’s the state’s playbook, minus the leather. Power’s not liberation—it’s a leash, and we’re begging for the collar.

This is the raw core of how the powerful view the subjugated. The sadistic “Dom” isn’t just a bedroom quirk—it’s a mirror to authoritarian rulers and the twisted systems they forge. Power rolls out in three brutal steps: Claim the upper hand from the jump. Lay down the law. Punish defiance, with force if needed. Add a fourth, if you’re feeling sly: Dress it up as love and care.

“I’m beating you because I adore you” isn’t just a line from a bad parent—it’s a psychological gut-punch, a double-bind that scrambles the mind. Imagine loving your tormentor, forced to see their cruelty as your fault: “If I’d followed the rules, he wouldn’t have had to hurt me. His whip proves my worthlessness, not his sickness.” That’s the game—shifting blame to the broken.

Politically, sexual sadomasochism lays it bare: the sadist’s glee is the spark, unvarnished, unlike the veiled sadism of states, reform schools, barracks, prisons, or toxic families. Christian Grey owns it: “Your submission thrills me—the more you bend, the higher I soar.” Power structures, though? They cloak their selfishness in fake virtue: “This is for your growth—I’m just setting boundaries.” Spare me the sermon.

Destructive power’s always got a touch of Grey’s vibe—it’s just less honest, denying its real fuel: the kick of cruelty. Fifty Shades caught flak for botching S&M’s truth, dismissed as soft porn by critics too tough for foreplay. But the SM-Handbook—penned by scene insider Matthias T.J. Grimme—suggests E.L. James served up a lite version. What’s gripping is its shamelessness, dodging moral filters.

“That tingle… that power… unmatched… divine!” gushes one practitioner. Another raves: “Every scream from that tortured woman egged me on—harder, unrelenting. I struck, I whipped, I humiliated in a sadistic, orgiastic frenzy.” Grimme calls blows “humiliating punishment, a flex of power and powerlessness, or a trance trigger.” Even Fromm’s unity-craving from Escape from Freedom gets a nod: “Some chase an out-of-body high, boundary-pushing that remakes them, revealing more of their depths.” It’s not just sex—it’s a warped transcendence.

Politically, the handbook’s role-play list chills: “Serbian soldier and Muslim woman, SS doctor and Jewish test subject, Daddy and naughty daughter.” Rape’s on the menu too, by mutual consent. The point? “Reducing someone to something lesser, filthier—a slave, a body part, a thing, an animal.” Grimme spins it rosy: “Humiliation, scorn, degradation cut so deep, the sexual rush can hit harder.” Freedom-lovers might shrug—two consenting adults, what’s the harm? But Christian doesn’t just woo Anastasia—he hooks her, makes her needy. “This is the only relationship I want,” he warns. Translation: Play along or lose me.

That’s coercion dressed as romance, pushing her past her limits. He’s polite, she’s sassy—a “slave at eye level” to soften the sting for readers, easing any shame. Harmless fluff? Hardly. It’s a cultural echo of creeping authoritarianism, gussying up control and harshness as virtues, coaxing the subjugated to grin through their chains.

Orwell’s torturer O’Brian gets it too, practically panting: “Always—don’t forget this, Winston—there’s the thrill of power, growing sharper, subtler. Every moment, that electric rush of victory, the feel of stomping a helpless foe.” It’s near-sexual—a dictator’s wet dream. Power’s not a duty; it’s a drug.

States peddle “protection” while tightening the screws—think lockdowns or surveillance, sold as care but reeking of glee. Critics who wave off S&M as private kink miss the point: it’s a blueprint for how power seduces and breaks, whether in bed or parliament. The rush isn’t optional—it’s the engine. And we’re kidding ourselves if we think the powerful don’t feel it too, just with better PR.

The Marquis de Sade, the twisted godfather of “sadism,” plunges us deeper into power-lust’s abyss with his novel Justine: “You don’t want your partner to feel pleasure—you want to leave a mark on them; the imprint of pain dwarfs that of joy… you see it, you wield it, you revel in it.” How quaint that “making an impression” rarely tops the list of power’s motives. Yet strip it bare, and that’s the pulsing heart: the thrill of bending another being, watching your force ripple through them. Like a boot-print etched in snow or the “ecological footprint” ravaging the planet, humans crave to stamp their will on others’ souls.

Your existence, your actions “matter”—and the more power you clutch, the deeper the gouge. A lover sways us with affection; O’Brian, chaining Winston Smith to a slab, carves with pain. Both wield power—different tools, same game. If power’s itch is to flex, to be felt, then inflicting pain outshines doling out pleasure. Joy needs a willing dance partner; pain thrives on a captive, a steep power gap no one escapes. Forcing someone to swallow torment? That’s power’s gold medal—raw proof you rule. “Leaving a mark” is nice; a brutal, indelible one’s better. Making someone endure the unbearable? That’s the tyrant’s crown jewel—because it’s never consensual.

Erich Fromm peels back the sadist’s skin:

“It’s the drive to seize total control, to turn another into a helpless puppet, to reign as their absolute lord, their god, doing whatever you damn well please. Humiliation and enslavement are just stepping stones. The ultimate rush is torment—there’s no greater dominion than making someone suffer, forcing them to choke on pain they can’t fend off.”

Power in this sick guise only smirks when it’s deified over its subjects. If it’s a kick for certain warped minds, don’t picture a tidy treat—like a nightly chocolate nibble, same size, same time. No, this is addiction, especially in cracked psyches.

The old dose won’t cut it after a while; they crave more, then more, then more. But empires hit walls—expansion stalls. Nietzsche’s “power-growth lust” needs a new fix. Orwell pegs two paths: swell the ranks of the subjugated, then burrow deeper, smothering every free thought, colonizing minds with the ruler’s script. Add a third, courtesy of de Sade: crank up the “impression”—the visceral dent you leave on the powerless.

Power’s direction—constructive or destructive—is one thing; its intensity, the sheer weight of its mark, is another. Go dark, and that mark bites harder, lingers longer.

Helmut Kohl and Mikhail Gorbachev sparked fleeting bliss with Germany’s reunification—wall down, beers up, a quick Volksfest buzz. Compare that to Adolf Hitler’s shadow, a black shroud over hundreds of millions, and the Wende’s cheer looks like a firecracker next to a nuke.

Destructive power seduces because suffering’s a bottomless well—politics can churn out misery on tap. Stymied by a bigger bully? No sweat—your legacy festers as transgenerational trauma, a ghost in the collective psyche.

In Germany, Hitler’s still the heavyweight champ of influence—his wreckage haunts them, shaping evasion, rejection, or rare, grim mimicry. That’s power’s pinnacle, and it’s no accident. Politically, states bank on fear over hope—control sticks when it scars.

Fromm insists there’s “no greater power over another than inflicting pain.” He’s underselling it. The real apex? Giving or snatching life itself. With enough clout, you dictate how others live; absolute sway decides if they live. Lust for killing? Let’s skip the taboo and eyeball the mundane: animal slaughter. Milan Kundera called its casual, industrial grind humanity’s grand flop.

Enter Florian Asche—lawyer, avid hunter—baring it all in Hunting, Sex, and Eating Animals: The Lust for the Archaic. “Isn’t chasing tail like stalking game?” he muses. “Might sex and hunting share the same primal wiring?” Then: “It’s not the hunter who’s erotic—it’s the hunt. The drive for prey, surrendering to it, fuels the passion. That’s its sensuality, steering our bedroom games too. Yielding’s the key—on the prowl or between the sheets.” He’s onto something—power’s pulse throbs in both.

Back to square one: the flimsy excuses for power-grabbing—duty, world-saving—stink of fraud. We don’t hunt to balance ecosystems. That’s not why we bother. It’s a flimsy alibi for urges deeper than deer quotas or green agendas… Imagine a guy shrugging off his wild sex life with, ‘I’m just ensuring humanity’s survival, spreading love, striking a blow against war.’ He’s full of it. Power freaks, though, blank out their victims’ worlds.

Asche doesn’t spare a whisper for the deer, boars, or hares he guts—mowing them down’s a legal power rush, topped only by, say, US Air Force drones overseas.

One of the slickest spiritual cash cows of the last three decades is James Redfield’s The Celestine Prophecy (1993)—a jungle romp masquerading as enlightenment. Our nameless hero hacks through Peru’s wilds, chasing a cryptic manuscript that’s supposed to crack open humanity’s future.

Part Indiana Jones, part self-help guru, he stumbles into the “9 Insights of Celestine.” One hooks me hard: “The Struggle for Power.” Redfield spins it as a brawl for life-energy. Our guy, juiced up on mystic vibes, starts seeing people’s auras—shimmering halos that dance and clash. During one spat, he clocks two auras duking it out:

“Their energy fields thickened, churned, like they were buzzing to some inner beat. As the argument heated up, the fields tangled. A solid point landed, and the winner’s aura sucked at the loser’s like a vacuum. The other fired back, and the energy sloshed home. Victory hung on who could siphon off the other’s field and gobble it up.”

Even if you scoff at auras, you’ve felt it: nailing a debate pumps you up; getting trounced leaves you limp. Total powerlessness—stuck, helpless—drains you dry. Two people clash in a chat—everyday stuff—and one walks away stronger, the other weaker, depending on who bends the vibe.

The trick to not bleeding energy—and maybe stealing some? Control. We’re always primed to pull every lever, clinch the win, keep the reins tight—no matter what. Nail your stance, and you’re invincible; flub it, and you’re sapped. Control someone, and you swipe their energy. You fuel up off their tank.

If that holds water, we’ve cracked power’s psychological code. Destructive power fattens the ruler while starving the ruled—a dynamic sparking endless scraps, verbal or bloody. It’s why people itch to argue, to dominate. This fight drives every conflict, from petty family tiffs to union showdowns to nations slugging it out.

Picture your body wrapped in a pulsing fog—call it life-energy, a neon shroud. In a clash, that fog drifts from the meek to the mighty. The timid lose; the brash gain. The gap widens—strong vs. weak—until the drained can’t muster a counterpunch. Economic theory nods again: power’s a zero-sum game—your gain’s my loss, like capital hoarding wealth while labor withers. Politically, states thrive on this—crush the weak, swell the elite.

Most folks are always hunting others’ energy. Some turn it into an art. These leeches hone dominance tricks, grazing on weaker fields like cows on clover. They’re brawl junkies—yet never tapped out, gorging on the vanquished’s juice. It’s not random; it’s strategy. Open fights wear you down—lose enough, and you’re toast. So, the savvy claw for institutional thrones—perches where victory’s baked in. A boss rarely flops; if a lackey out-talks them, they’re fired. Smart underlings don’t crow too loud—the boss holds the whip.

Power gigs are energy subscriptions—automatic refills. When the gap’s wide, the top dog’s a lock to win the “energy war.” Cue the stampede for power jobs—politicians, brass, cops, bureaucrats, jailers. Even a petty clerk, armed with rulebooks, smirks as clients flail in red-tape nets. Their pleas bounce off; the clerk’s badge trumps all. It’s a gushing energy well—petty tyranny pays dividends.

During COVID, feeling drained? Join the enforcement squad and watch your tank overflow. Mask rules outdoors? They’d shove them down throats with glee. Citizens balked, instincts kicking, but the law crowned the enforcer king—snapping resistance was an energy buffet.

Lockdowns morphed everyone into wardens or inmates—a nationwide prison play. Shopkeepers and baristas got drafted as state goons, barking “the rules”—no mask exceptions, scribble your name, keep your distance—or else. They doubled as vaccine bouncers, shooing the unjabbed. Sure, the state twisted their arms—duck the role, and your livelihood’s toast in this coercion racket. But don’t kid yourself: not all these mini-dictators squirmed. Some savored the petty power spike, grinning as they flexed. Energy boost, maybe? When the system hands you a club, swinging it feels too damn good. No altruism here—just parasites in aprons, fattening on compliance.

Some might sneer that leaning on an esoteric blockbuster like The Celestine Prophecy—where one soul siphons another’s energy to dominate—proves nothing. Fair enough—it’s no smoking gun. It reads more like a cosmic spoof. But don’t dismiss satire so fast; its barbed exaggeration often skewers deeper truths.

Haven’t you ever staggered away from a verbal thrashing by some overbearing jackass, feeling like they sucked your soul dry? Or sat in a room where loudmouths hog the air, leaving you no space to breathe, let alone shine? Flip it: when you’ve owned a debate, landed every punch, don’t you strut off buzzing with a jolt you didn’t have before?

Deny it all you want—your gut knows the score. This isn’t just woo-woo fluff; it’s human nature bared. Psychologists like Franz Ruppert back it up in hard-edged terms—his piece “The Tyrant’s Loneliness” doesn’t mess around. He dives past petty squabbles into the warped minds of power-sick freaks.

Picture this: the untouchable despots—always in control, answers at the ready—started as sniveling kids craving Mommy’s hug. When love got yanked away, those needy brats didn’t just sulk; they curdled into tyrants or basket cases—often both. Terrified of facing that buried ache, they choke everything in reach. No love? Fine—they’ll make you feel them through force. Ruppert’s blunt: Tyrants and dictators don’t register the pain they dish out—they’re numb to their own. Accountability? Forget it. Their victims? Disposable, erased from memory the second the screams fade.

Cut off from their own juice, they vampire off the dominated. It’s a vicious cycle with teeth—politically, it’s a wrecking ball. They bank on dependence. Political, economic, social, psychological—they want you hooked.

Ruppert flips the script: Truth is, they’re the junkies—empty without the fight. Strip away their targets, and they’re husks, severed from their own guts, gorging on external hits. Perps feed on victims’ life-force. Starved of their own, they need a steady drip from others—or they deflate like a punctured balloon. Resistance? That’s their jet fuel—they crave it. Funny, right? You’d think pushback weakens a ruler. Nope—breaking a fighter’s spirit is the tyrant’s cocaine.

Imagine a poker game: you ante up, they raise, you double down. Against a stacked deck, you’re bled dry—your energy’s their pot. “Winner takes all,” and they’re grinning. Power’s a market—scarce resources (your vitality) get snatched by the top bidder. Politically, states rig the table—dependence is their currency.

Quick surrender softens the sting—less energy lost if you don’t squirm. Explains why so many roll over fast. Resistance feels futile, so why bleed out? But drag it out, dig in, and the dominant’s victory gets sweeter. Power-lust fattens on defiance; crushing it is the prize.

Ever notice how bosses, cops, or bureaucrats don’t flinch at breaking you? Healthy souls crave consent—give freely or keep it. Sick ones drool over defiance—it’s a bigger haul. Nothing’s crazier than screwing with someone’s psyche, shattering it. You churn out wrecks—unpredictable, self-destructing, begging for control. Tyrants rule a madhouse, not a future. They drag everyone into the pit, chasing a ghost of what they secretly crave. Worshipped? Sure. Loved? Never.

Fromm’s got a secular spin: we’re lonely, cast out of Eden—family, tribe, faith—into a void. We grope for new ties; the rotten ones turn sadistic or masochistic. Together, sure, but not equal—the top dog rides the bottom as an “energy pump.” It’s a warped Eden redux—hell for the crushed.

Fromm’s no mystic; his “paradise” is primal bonds, not halos. Take it spiritual or not: worldly, the tyrant’s love-starved, scarred by pain, forcing a grotesque facsimile—like Priklopil’s dungeon “romance”—or ditching feelings to leave a mark through agony. Think Wagner’s Alberich, ditching love for the ring. Spiritually, he’s rebelled from the Source—God—aping Satan’s mythic tantrum. Goethe’s Faust prologue has the Lord betting Mephisto: “Lure this soul from its root, drag it down your path if you can.” The Lord trusts our core’s solid—“A good man, even groping blind, knows the way.” But what about those truly ripped loose? Meet the vampire—mythic, bloodsucking, and oh-so-fitting. Power’s no savior; it’s a leech, and we’re the veins

Vampire tales always pack a double punch: the victim gets drained, then turns vamp. Let’s stick to the draining bit for now. We’ve all met those soul-suckers—people who leave you ragged while they strut off, brimming with zest. They might bulldoze you with demands or smother you with clingy helplessness—either way, you’re tapped out, they’re topped up.

Entire books dissect this “energy vampirism.” Remember The Matrix? Humans as batteries, juiced by cold machines—capitalism’s grim parody. When you’re a cog, forced to fuel someone else’s rise, the vampire myth bites hard. It’s not always cash—exploitation’s old tune—but power itself can bleed you dry, as we’ve seen.

Take Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), a standout bloodsucker flick. He sticks close to the novel but slaps on a prologue with teeth: Dracula, a Crusades-era Romanian noble, curses Christianity after it damns his beloved Elisabetha to hell. He rams his sword into a chapel cross—blood gushes—and he’s cursed to roam as an undead leech, thirsting for lives he drags down with him. Only Mina, Elisabetha reborn, can redeem him across an “ocean of time.” He’s no mere fiend—more a fallen angel, aching for love. Pity and dread wrestle over this “hero.”

Symbolically, vampires mirror souls severed from the “source”—love, life-force—sometimes for reasons we can grasp. It’s a curse, not a perk: they’re junkies, raiding others’ energy to dodge collapse. No autonomy—they’re stuck staging dominance dramas, roping in prey to keep from shriveling.

That’s why power’s grip is a chokehold few shake off. Now pivot to the state and its citizens. Why do governments hammer demands met only with gritted teeth, coerced by fines or jail? Why do enforcers—military brass, COVID rule cops—relish snapping wills, a pathetic spectacle that should sicken even them? Why stage these clashes nonstop, banning what most shrug off as harmless? Dig deeper: there’s a side hustle here, and for a warped few, it’s the main gig. Breaking the helpless feeds them—a toxic, heady brew. It’s why evil clings like damp rot across eras and continents.

They don’t force compliance despite resistance—they crave it because of it. Smashing defiance is the sick thrill. Righteous fury—at a bullying boss or a smug COVID snitch—is pure, a roar of self-worth. But choke it down, mumble “okay,” and you brew the dark sludge power freaks guzzle.

Sure, this lens feels alien to many. Still, humor me: scour politicians’ moves for that glint of power-lust glee. The pile of despotism—big and small—across history’s ledger is too damn heavy to swallow “noble intent” whole. Power’s a parasite—states don’t uplift; they extract, like landlords bleeding tenants dry. Control’s the drug—resistance just spikes the high. Don’t buy the savior act; it’s a fangs-out feast.

Why Your Support Matters:

Substack is at risk of becoming another mindless scroll-fest like TikTok or Instagram, drowning out the thoughtful, long-form content we cherish. If you value real intellectual writing over clickbait, act now:

Like and Restack the work of authors you admire—every click boosts their visibility.

Comment politely to spark conversation and lift their reach.

Share your favorite pieces far and wide to drown out the shallow noise.

Don’t let Substack devolve into cat videos and rants. Fight for its soul—starting today.

Thank you; your support keeps me writing and helps me pay the bills. 🧡

Thanks for this excellent deep dive into a fascinating subject! I appreciate how you've approached it from many different angles.

"They bank on dependence. Political, economic, social, psychological—they want you hooked."

This, I think, is key to adapting and developing potential solutions, given where we're headed as a society. Since dependence is submission to the domination of the entity we're depending on, developing self-sufficiency as much as possible is at least part of the solution. Perhaps the only one we have at this point. Our ancestors knew this - wisdom many religion-based communities such as the Amish have retained. Growing a garden is a great start! He who controls the food, controls the people.

WOW Lily. This has to be your most POWERFUL piece yet. The depth you attain with the subject matter are unrivalled IMHO and make it a satisfying pleasure to financially support such dedicated work. I have a vested interest here, as this subject is something I have been researching, in light of current global activity, and you have helped open and educate my mind. God Bless you Lady.